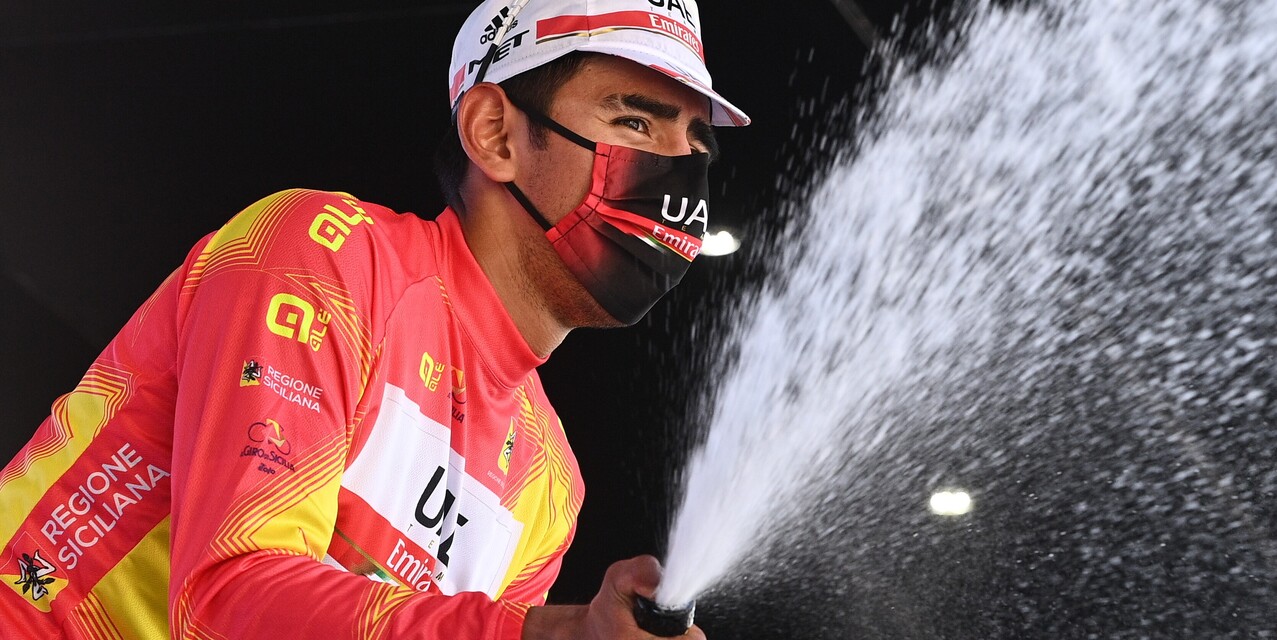

It has been a good year for riders from indigenous backgrounds. Neilson Powless of the Oneida nation won the Clásica San Sebastián in July and made the decisive break in the Worlds on Sunday. Richard Carapaz, of Pasto heritage, became Olympic champion and emulated another indigenous rider, Nairo Quintana, proudly Muisca, by finishing on the podium of the Tour de France. Today another Native American, 22 year old Charles-Étienne Chrétien of Rally Cycling, showed himself by joining the breakaway, winning the only mountain prize of the day, and taking the jersey.

A member of the Innu people (called the Montagnais by their French colonial masters) who live in Quebec and Labrador – territories they call Nitassinan (“Our Land”, ᓂᑕᔅᓯᓇᓐ) or Innu-assi (“Innu Land”) – Chrétien won the Junior Canadian National Championships in 2017 and celebrated with a Juan Antonio Flecha-style “bow and arrow” gesture. He explained after that victory, “That salute means a lot to me and my family. Bow hunting is a tradition for North American Aboriginals. That salute was a kind of connection and gesture of appreciation to aboriginal communities.”

By wielding globalised sport as a defensive weapon against assimilation, these riders are so numerous now they could almost be called a movement.